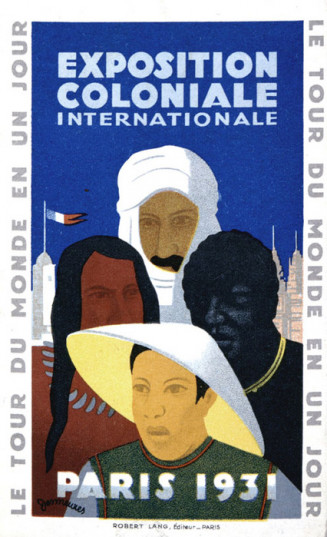

The Colonial Exposition of 1931

The exposition will have achieved its goal if, as a result of it, many young people develop a desire for a career in the colonies!

The exposition in the Bois de Vincennes followed the tradition of universal expositions and colonial expositions, whose purpose was to exalt the technological and civilising power of European and North American countries. Devoted exclusively to the colonies, it was held from May to November 1931, and welcomed almost 8 million visitors for 33 million tickets sold.

The project was not new, since a member of the French parliament had submitted a similar project back in 1910, and it had been taken up again after the war. Meanwhile, Marseille was also developing its own project, which eventually took shape as the 1922 Colonial Exposition in the southern French city. The Parisian project was revived in 1927 with the prestigious Maréchal Lyautey as its general commissioner.

What could be seen there?

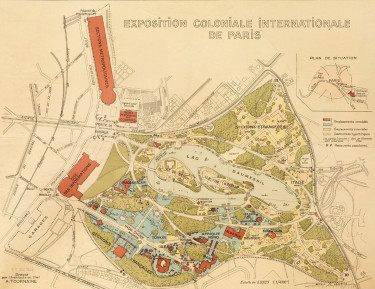

Taking the form of a huge public show, a true city within a city, the six-kilometre-long exposition, three and a half kilometres wide, with its two hundred buildings representing the different French colonies and territories, stretched over an area of 110 hectares. Line 8 of the Paris Metro was extended for the occasion, with the creation of the “Porte Dorée” station. The Palais des Colonies, the only building designed to outlast the event, was the hub of the exposition, presenting, on the one hand, the history of the French empire in a “retrospective” section and, on the other, in a “summary” section, its territories, what the colonies had brought to France, and France to the colonies.

A small train enabled visitors to get around the exposition quickly: starting with the foreign section with the Portuguese pavilions, Belgium’s Congolese huts, Holland’s Javanese temple, Italy’s tripolitan Basilica, and the USA’s Mount Vernon plantation. The United Kingdom was absent, having declined the invitation, despite being urged to attend by Lyautey (it merely accepted a booth in the Information area). The British government claimed to have other financial commitments, and negotiations were underway to determine the status of the Commonwealth.

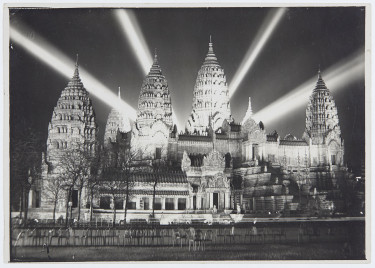

The train then continued on to the French empire, presented in all its majesty. All along the grande avenue, the pavilions of the “old colonies” (West Indies, Guyana, Reunion, French Indies, Oceania) were set up, leading to the highlight of the exposition, the temple of Angkor, with the spire of its central tower reaching up 55 metres. The French West Africa pavilion, inspired by a fortified palace in French Sudan (or by the Great Mosque of Djenné) was another spectacular reference point. In contrast, the French Equatorial Africa pavilion was much more modest, as if to avoid emphasising some of its tragedies, starting with the terrible construction of the Congo-Ocean line around the same period. The Morocco pavilion, of particular importance to Lyautey, was another of the exposition’s must-visits. In the spirit of a Marrakech palace, this pavilion aimed to present a “modern Morocco”, a new country, electrified, at the cutting-edge of progress.

To help make the event lively and attractive, visitors could enjoy a number of special attractions, and the dance performances were one of the most popular of these. In each section, inhabitants of the colonies brought to the site re-enacted life in reconstructed villages. Craftsmen worked in front of the public, while others ran souvenir stands. Although the approach taken by the 1931 exposition did not strictly speaking involve the recreation of the “human zoos” that had become outdated, whereas they had been common in previous colonial expositions, the goal was still to put men and women on display as a way to better assert the power France had over them.

Nevertheless, at the same time, the installation of a “Kanak village” in the Jardin d’Acclimatation in the Bois de Boulogne ¬– an initiative of the Fédération Française des Anciens Coloniaux, independent of the actual Colonial Exposition – caused an uproar. The Kanaks felt humiliated at being attributed the role of cannibals, and several of them died of illness due to the deplorable sanitary conditions.

The three narratives of the Colonial Exposition

In his book Le goût des autres. De l'exposition coloniale aux arts premiers, the anthropologist Benoît de l'Estoile distinguishes three types of narrative in relation to colonised subjects, presented simultaneously in the exposition: one is "evolutionist", the other "primitivist", the last one "differentialist".

In the evolutionist case, the colonial mission is justified by the savage nature of the indigenous people at the time of the conquest. Thanks to the beneficial action of European civilisation, Africans, in particular, could leave their childish state behind at an accelerated speed, and enter into the course of history. The evolutionists, like the others, based their theory on a hierarchy of races, but presented it as part of a progressive plan, in the sense that the “inferior races” were capable of evolving favourably under the benevolent guidance of their colonisers.

The primitivist argument tended to emphasise origins, which were highlighted by the “primitive arts”, precious evidence from people who had remained at the dawn of humanity, outside of history, in fusion with nature. This narrative was the distant heir to the “noble savage” argument: someone outside civilisation, and therefore not perverted by it, but also deprived of what makes one a human, in other words change and the experience of history.

The differentialist narrative, for its part, celebrates the diversity of cultures, and assigns a mission of preservation to colonisation. The question of racial hierarchy takes a back seat behind the notion of "difference", yet it is not absent, far from it. Maréchal Lyautey leaned towards the differentialist perspective. For him, colonisation was to maintain differences while surpassing them within a common political framework, that of the French empire.

Inside the Palais de la Porte Dorée, the fresco by Ducos de la Haille is a clear expression of the evolutionist perspective (colonisers can be seen bringing the benefits of civilisation), the primitivist perspective (the colonial world is depicted as an Eden where humans live in communion with nature and animals) and the differentialist perspective (illustrating the variety of cultures from one end to the other of an empire where “the sun never sets”, as the British would say).

A situation kept under wraps

The true colonial situation was kept under wraps. A lid was kept on any mention of colonial violence, the crimes taking place, any wrong committed in the name of civilisation, as well as the ordinary situations of domination and exploitation such as forced labour. Nor was anything said about resistance from colonised peoples either in the past or while the exposition was taking place, at the very time when persistent cracks could be felt spreading across the colonial empires. And lastly, nothing was said about the surreptitious changes coming to light in the colonial world, particularly in the cities, where new cultures, including music, were gradually developing, freeing themselves from the oppressive paternalism of the masters. The propagandist nature of the Colonial Exposition could not include anything relating to the secret or discreet life of colonised peoples, their own spaces, the worlds of the night, the murmurs and whispering.

The surrealists were in the forefront in denouncing the exposition: “don’t visit the Colonial Exposition!” was the watchword in a pamphlet notably signed by Aragon, André Breton, René Char and Paul Éluard, printed two days before the exposition started. The surrealists and their communist allies were the most radical in their denunciation since they criticised the very principle of colonisation, unlike the socialists, and even some colonial administrators, who instead lashed out at its excesses. Many visitors to the exposition looked at it with a critical eye, without being taken in by the colonial propaganda. The Senegalese poet and politician Senghor for example, who was just finishing his literature course at the time and could be seen walking up and down the avenues of the Bois de Vincennes, lost in thought.

In autumn 1931, surrealists and communists set up a counter-exposition entitled “The truth about the colonies”, in what is now Place du Colonel-Fabien, the site of the headquarters of the French Communist Party today. This counter-exposition lambasted the official exposition, using signs to spotlight the crimes of colonisation and the precarious economic situation of the colonies, which were certainly not the “shield against an economic crisis” that the government claimed they were. Anti-colonial struggles were also given a prominent place, from India to Morocco via the “lynching of negroes” in the USA. Another room paid tribute to the USSR’s Policy on Nationalities, at a time when Stalin was consolidating his power, leading a merciless oppression of the kulaks and starving millions of Ukrainians. The counter-exposition would only attract a few thousand visitors, far from the crowds of people rushing to the Porte Dorée.

Pap Ndiaye, 2022